Corruption in Healthcare

Introduction

Transparency International defines corruption as the “abuse of entrusted power for private gain,” a definition particularly relevant to healthcare where entrusted power is extensive and its misuse made-easy by large financial flows, complex processes, information asymmetry, and weak monitoring structures. These vulnerabilities create fertile ground for both administrative and professional misconduct.

Approximately $455 billion of the $7.35 trillion spent on health care annually worldwide is lost each year to fraud and corruption. Furthermore, the OECD estimates that 45 percent of global citizens believe the health sector is corrupt or very corrupt.

Typologies of Corruption

Six core forms of corruption exist and interact with clinical and administrative processes at different levels of the healthcare system.

Bribery. Illicit payments to accelerate services, secure appointments, or influence clinical or administrative decisions.

Collusion. Secret agreements among bidders or officials that distort procurement, pricing, or regulatory approvals.

Extortion. Coercing individuals into paying for services that should be free or threatening reduced quality unless payment is made.

Embezzlement. Diverting public funds, medicines, equipment, or user fees for private benefit.

Fraud. Falsifying medical records, insurance claims, treatment reports, or supplier documentation.

Favoritism and Nepotism. Undermining meritocracy by appointing, promoting, or awarding contracts based on personal ties.

Levels of Corruption

Corruption manifests at four interconnected levels.

Petty corruption. Common in frontline settings—informal payments, manipulation of waiting lists, and document falsification. While low in individual monetary value, its cumulative impact is large.

Grand corruption. Involves senior officials who manipulate tenders, investments, or appointments, redirecting resources on a large scale and shaping sector priorities for political or financial gain.

State capture. Occurs when powerful private or political actors influence policies, regulations, or legislative decisions to benefit specific interests. Examples include shaping drug pricing regulations or licensing frameworks.

Professional corruption. When clinicians use their power to manipulate care to their benefit. Examples include: Accepting inducements from pharmaceutical companies, performing unnecessary procedures for profit, preferential treatment of private-paying patients, issuing falsified medical documents.

Drivers of Corruption

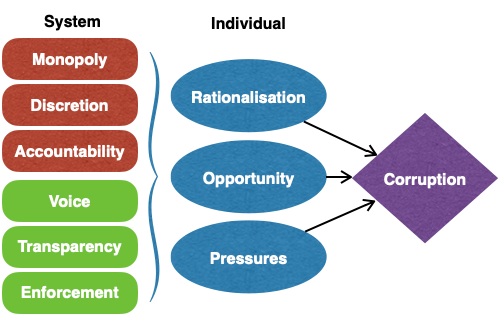

According to Vain 2008 corruption arises from a combination of individual and system factors that lead to abuse of power for private gains.

Opportunities for corruption are created when systems permit monopoly of power with opaque decision-making and poor accountability.

These opportunities are augmented by weak citizen / patient voice coupled with lack of transparency / information and ineffective enforcement systems.

Simultaneously, individual attitudes, social norms, cultural logics, and personality traits may normalise or justify corrupt acts, especially in contexts of economic hardship or eroded public-service values.

Pressures such as financial need, low salaries, debts, or client and supplier demands can also push individuals towards corrupt behavior, indicating that effective anti-corruption strategies must address not only institutional weaknesses but also human factors, incentives, and cultural norms.

Identifying and Diagnosing Corruption

Several analytical tools are available:

Family Tree Analysis (FTA). Maps networks of familial, social, and business relationships to detect conflicts of interest and patronage. Particularly relevant for identifying influence networks in pharmaceutical regulation, hospital administration, or tendering committees.

Value Chain Analysis (VCA). Tracks processes from start-to-end to help identify where inefficiencies, fraud, or leakage occur. Procurement and supply chain processes often pose the highest risk.

Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS). Quantify leakage in fund flows from central institutions to local providers. PETS have been used globally to identify losses of up to 80% in some health sectors.

Accountability Linkages Mapping. Illustrates relationships between key stakeholders in healthcare. Gaps in these linkages often correspond to areas with limited oversight and heightened corruption risk.

Measuring Corruption

Corruption can be assessed through:

Perception-based indices, such as the Corruption Perceptions Index and Worldwide Governance Indicators.

Experience-based barometers, including Afrobarometer and Global Corruption Barometer.

Sector-specific integrity metrics, which focus on procurement, supply chains, human resources, and financial flows.

Tackling Corruption

A four-faceted model can be followed:

Awareness and Education

-

- Patient rights education.

- Ethics and integrity modules in health professional curricula.

- Public awareness campaigns.

Preventive Measures

-

- Transparent procurement system with digital disclosure.

- Strengthening community participation.

- Embedding anti-corruption in national health strategies.

Detection Mechanisms

-

- Independent audits and monitoring units.

- Complaint-handling mechanisms.

- Protected whistleblowing systems.

Sanctions

-

- Administrative penalties for misconduct.

- Criminal prosecution for severe cases.

- Professional disciplinary actions.

Integrating Anti-Corruption Solutions

An effective strategy must operate across the six health system building blocks:

-

- Leadership / Governance – conflict-of-interest regulation, transparency mandates.

- Health Financing – eliminating budget leakages and fraudulent claims.

- Human Resources – reducing absenteeism and job purchasing,.

- Service Delivery – removing informal payments and improving hospital management.

- Medical Products and Technology – securing supply chains and ensuring procurement integrity (e-procurement).

- Health Information Systems – digitalisation to reduce manipulation and enhance public reporting (e-payments, e-complaints, e-health cords).

Reading Material

-

- NAM. Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide. 2018.

- DFID. Addressing corruption in the health sector. November 2010.

- Vain T. Review of corruption in the health sector: theory, methods and interventions. Health Policy and Plan. 2008;23:83-94.

Disclosure

This monograph is based on a lecture delivered to the Health Governance Diploma. The monograph lecture-derived text has been generated using AI and human edited to fit purpose and allocated space.